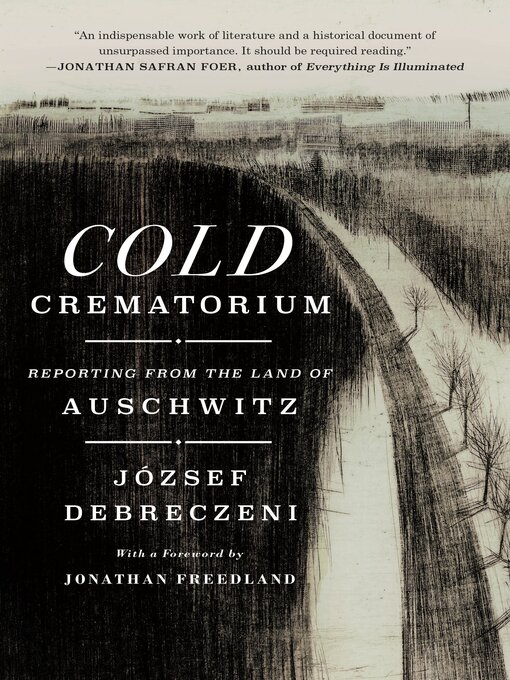

National Jewish Book Award finalist and one of the New York Times Book Review's 10 Best Books of 2024

A lost classic of Holocaust literature translated for the first time—from journalist, poet and survivor József Debreczeni

"As immediate a confrontation of the horrors of the camps as I've ever encountered. It's also a subtle if startling meditation on what it is to attempt to confront those horrors with words...Debreczeni has preserved a panoptic depiction of hell, at once personal, communal and atmospheric." —New York Times

"A treasure...Debreczeni's memoir is a crucial contribution to Holocaust literature, a book that enlarges our understanding of 'life' in Auschwitz." —Wall Street Journal

"A literary diamond...A holocaust memoir worthy of Primo Levi." —The Times of London

József Debreczeni, a prolific Hungarian-language journalist and poet, arrived in Auschwitz in 1944; had he been selected to go left, his life expectancy would have been approximately forty-five minutes. One of the "lucky" ones, he was sent to the right, which led to twelve horrifying months of incarceration and slave labor in a series of camps, ending in the "Cold Crematorium"—the so-called hospital of the forced labor camp Dörnhau, where prisoners too weak to work awaited execution. But as Soviet and Allied troops closed in on the camps, local Nazi commanders—anxious about the possible consequences of outright murder—decided to leave the remaining prisoners to die in droves rather than sending them directly to the gas chambers.

Debreczeni recorded his experiences in Cold Crematorium, one of the harshest, most merciless indictments of Nazism ever written. This haunting memoir, rendered in the precise and unsentimental style of an accomplished journalist, is an eyewitness account of incomparable literary quality. The subject matter is intrinsically tragic, yet the author's evocative prose, sometimes using irony, sarcasm, and even acerbic humor, compels the reader to imagine human beings in circumstances impossible to comprehend intellectually.

First published in Hungarian in 1950, it was never translated into a world language due to McCarthyism, Cold War hostilities and antisemitism. More than 70 years later, this masterpiece that was nearly lost to time will be available in 15 languages, finally taking its rightful place among the greatest works of Holocaust literature.

- Popular titles

- 2025-26 Sunshine State Young Readers Award Gr. 6-8

- 2025-26 Florida Teen Reads

- See all ebooks collections